“The mission is so near and dear to me as it relates to transformative health and the potential impact on individuals and families and communities. We are all interconnected in some way.”

Joyce Ann Bell Winkler, R.N., MPH, has been eager to learn and lead since before she was old enough to attend school.

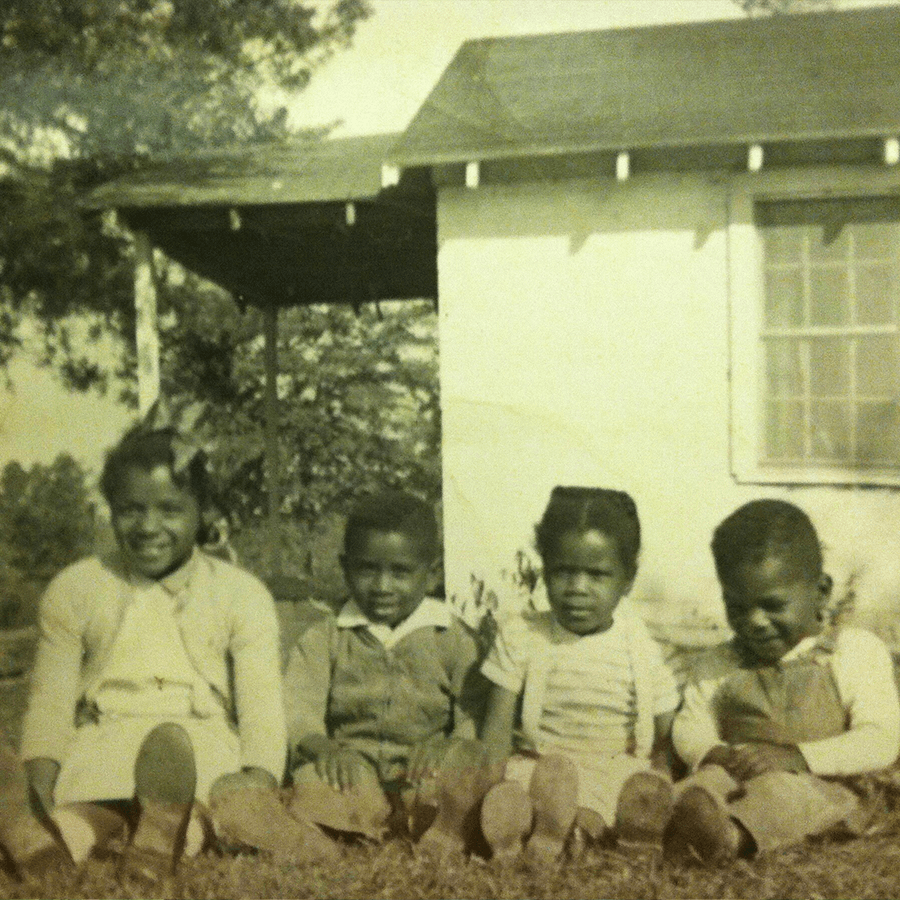

At age 4, Winkler convinced her mother to let her accompany her older brother Leonard Jr., on his first day of school. Their mother agreed and along with their older sister, they headed to the school bus. Once in the classroom, the teacher informed an enthusiastic Joyce that she would have to wait a year before coming back.

And wait she would.

Education was her bridge, one her parents helped build and promote. From a young age, Winkler was aware that going to school in her rural South Carolina community of Ridge Spring was an expectation. Classmates were absent at times as they were needed to work in the cotton fields and peach farms. In 1965, when the opportunity to attend—and integrate—the larger, all-white school in Aiken County became available, her parents were quick to sign up their children. Winkler started in 7th grade, accompanied by her older brother and sister and several cousins.

In October 2021, Winkler organized the 50th anniversary of her 1971 high school graduating class, which made local news as the school’s first fully integrated graduating class. At the festive reunion, she reconnected with high school classmates, many of whom remained in the small agriculture town after graduating. Winkler left to pursue a 40-year nursing career with positions in administration and management, teaching, and research.

Until her retirement in 2018, Winkler was based in Columbia, South Carolina, for the last years of her career doing what came naturally: leading. She was the principal investigator for the All of Us Research Program at Eau Claire Cooperative Health Centers Inc., a Federally Qualified Health Center.

“I feel connected to this program as I started at the beginning when it launched. I’m intrigued not only by what this program can do for me and my family, but what it can do overall for the health of communities across the country. We are all interconnected in some way.”

Participant Ambassador

Winkler has been an All of Us participant ambassador since 2021, informing her community about the potential to improve health care through widespread participation. The program seeks to enroll one million or more participants who reflect the diversity of the country. Participants can choose to share a broad range of health information. Their contributions have helped build one of the largest, most diverse databases of health information that researchers can use to study health and disease.

Winkler helped the program prepare a new survey in November 2021, asking participants about various social and environmental factors, including neighborhood safety, access to food, experiences with health care, discrimination, and daily work and living environments. More than 117,000 participants responded, giving researchers important data to better understand the connection between these daily lived experiences and the impact on overall health.

Witnessing the Personal Impact of Diabetes

Growing up on her family’s 130-acre farm, Winkler saw first-hand the health impact of her environment within her extended family. The prevalence of diabetes and heart disease persists, impacting her father, her siblings, as well as extended family members. Treatments, preventative options, and overall health care access have been largely beyond reach in her community. In retirement, Winkler returned to her childhood farm to care for her mother, who passed away in November 2020 at age 90. Her father died in 1998, at age 71, after a long battle with diabetes. Just 18 days later, she lost her oldest sister, who was 49, to complications of diabetes and lupus. Both her paternal grandparents endured amputations from diabetes, as did her father.

“In my small community, diabetes impacts nearly every family I know,” Winkler said. “It’s almost a normal situation. I think we need to encourage people to talk about it. The more information we share, the more we can encourage screenings and manage the disease.”

As of November 2023, new All of Us data from electronic health records shows that nearly 34,000 program participants are living with type 2 diabetes. Almost 55,000 participants indicated that type 2 diabetes has affected a close family member. The information can provide researchers with insights on diabetes risk and treatment response.

Researchers from Florida A&M University used data from electronic health records and surveys to identify diabetes patients at highest risk of a heart attack, stroke or heart failure. For Winkler, sharing the research findings with community members can raise awareness about prevention strategies and encourage more people to share their health experiences.

The opportunity to propel research has long motivated Winkler to pursue a nursing career and to continue promoting the program. Education has always been a driving force.

Integration

The experience of changing schools and environments would test and strengthen Winkler's resilience and leadership potential.

“It was so impactful and probably was the one experience that helped mold me, teaching me a lot about who I am as a person,” Winkler said. The transition from her familiar community public school to a larger unfamiliar setting was overwhelming, at times, she said.

“It was hostile on some days, but not to the point where it threatened my safety and security,” Winkler said. “Words were said, and names were called, and even whispered, but there was never a physical confrontation.”

The transition was even more stressful because her best friend throughout her elementary school didn’t join her until the following year because of transportation issues. The seating in the classroom proved a major obstacle. Back at her old school, she always chose to sit in the front row to show the teachers how eager she was to learn. But in her new school, the front row was taken, so were the next rows. The only available seat was in the back of the class, challenging in many ways, as she was always petite in height. Traditionally, the kids who sat in the back were the ones who didn’t want to concentrate and tended to distract the class.

She quickly noticed that a couple of girls who sat near her would look at her paper whenever there was a test. She thought they might need help with the lessons and looked forward to talking to them at recess.

“In my little mind, I thought maybe they’ll be more friendly to me, and I can help them with schoolwork,” Winkler said. “Maybe they will even sit with me in the cafeteria.”

It didn’t take long for Winkler to realize they were only interested in getting what they needed: the correct answers. So, at age 12, she decided to teach them a different lesson.

“I let them cheat off my paper,” Winkler said. Then she erased all the answers and turned in a corrected version. “I passed. They failed. I wasn’t trying to be ugly, but you know there’s a price to be paid when you want to take advantage of people and you think you can get away with that. That’s not right.”

“If all you wanted from me was an answer to a question, but you didn't really want my friendship, you really didn't want to acknowledge me as a human being,” she said. “I'm going to have to deal with you differently.”

This confident, no-nonsense spirit propelled her throughout her education and professional nursing career. Winkler wasn’t shy or afraid to get involved. She joined the girls’ basketball team and the school band. “I asked my parents to get me an instrument so I could join the band,” she said. “I saw no reason to sit on the sidelines and just feel sad and lonely.” She took up the clarinet.

Despite her petite height at barely 5 feet tall, she was a highly competitive basketball player and was named most valuable player in 7th grade. “I still have my little trophy.”

There were days when she came home from school and let it out, by herself. “I would go to the bathroom and cry. I didn’t want my parents to see me.” But she went back every time. Going to school was a must-do in her mind—a ticket to greater possibilities, beyond the farm, which was always a central focus on family life. After school and before starting homework, she and her five siblings were out in the field picking cotton. She remembered one afternoon, her father was angry that they had been playing in the fields, failing to pick enough cotton. He punished them by not letting them go to school the next day.

“Well, me being stubborn Joyce, I got dressed the next morning and started heading to the bus stop,” Winkler said. When her siblings asked where she was going, she confidently replied: “I’m going to school.” She began running up the field for the bus when she noticed the bus driver, not seeing all the siblings waiting, pulled away. “To this day, my brother still remembers me yelling, ‘Wait, I’m coming to school.’” She didn’t go that day, but it was the last day her father pulled his children out of school as punishment.

In 8th grade, her best friend Warrena Stywaskee (Stu) Broadnax Hankinson joined her, and they were a dynamic duo, joining sports teams, the band, choir after other activities. “My life became so much better. We did everything together,” Winkler said. “We joined every club there was. I just knew I was going to be fine.” They sang at their graduation together, “Just a Closer Walk with Thee.”

In their junior year of high school, the two best friends took their most adventurous step together, taking a special driving test at age 16 to become school bus drivers. They saw a sign near the bus stop that the company was looking to train new drivers. One of the bus drivers told them that they were more interested in training girls. “The boys just wanted to mess with the gears,” Joyce said they were told. When they found out that they were going to get paid a paycheck at age 16, they couldn’t turn down the chance. The two took a test and began training, before telling their parents.

“Remember, I grew up on a farm, so I was used to driving my daddy’s trucks and large vehicles,” Winkler said. Her friend’s dad had a truck as well. “She was gutsy and, well, we were used to doing everything together.”

They started driving in 1970, the year before graduation. In her senior year, she would drive the bus, park the bus, get off and go to class. She was dismissed early at the end of the school day to get the bus back and load up students. Her younger brother was her bus patrol on the bus. Winkler drove for the migrant program for two summers following graduation for children ages 2-7. The older children had to work in the fields.

“I drove 100 miles a day,” Winkler said. “I think about that now, and I scare myself, how does that happen? “I had 30-40 kids on the bus that I was responsible for. I was 17.”

Winkler, at 5 feet 3 inches, had to sit on a pillow to reach the pedals. One rainy summer day, the bus broke down. This was before cell phones and some homes didn’t have telephones either.

She lined up the children, ages 3-10, “like a choo-choo train,” she said, and had them walk perhaps a mile. She was able to find a home that had a phone to call for assistance.

Winkler and Stu were college roommates and remained best friends, despite their love of rival football teams. Winkler was with Stu at her side in her home when in 2012, her best friend passed away from bladder cancer. “I remember even at the end, she had me laughing. She said, ‘when I get up there, God is gonna have to tell me why I got an old white man’s disease.’”

Family

Winkler has two grown daughters and nine grandchildren. Rozalynn, born in 1977, lives in Greensboro, North Carolina, and is the executive director of a community theater. Jennifer, born in 1981, has a master’s degree in social work and a master’s in public health administration and is the director of a health insurance Medicaid program in Columbia, South Carolina.

After Winkler’s mother Annie Mae Bell passed away, Winkler and her husband Preston Winkler worked together to create a memorial on the farm to honor her mother. They built an 8-foot fountain with dozens of steppingstones leading up a path to the fountain. They asked her mother's grandchildren for ideas on what to name the garden and the youngest, Angela, 25, a music major, had the one they chose: "Annie’s Amazing Grace Garden." Angela played the song at a December 2020 memorial service dedicating the garden.

at a December 2020

memorial service

dedicating the garden

“Most of my personality comes from my dad, who was extroverted and energetic,” Winkler said. “But as I watched my mother handle those losses of my father, and then my sister, I saw her quiet energy and courage. I do believe as difficult as life can be, we have a choice on how we take and view these experiences. My mother had this beautiful positive demeanor. I find as I get older and go through losses and difficult situations, even though I still have a lot of my daddy’s visionary, take-charge, get-done attitude, I was blessed to be with my mother and will treasure her gifts.”

Building a Bridge: School Involvement

In retirement, Winkler has come full circle, returning to the school where she learned to lead. Again, she joined her older brother Leonard Jr., who was an advisor with the school’s agricultural department. Together, the pair aim to show students how their agriculture community can offer multiple different career opportunities, in science, marketing, and business.

“The key that I want students to take away is the importance of education,” Winkler said.

She remembered her parents taking all six children in their 1960s Chevrolet to the World’s Fair in New York. “My parents made sure they exposed us to things that gave us that bigger perspective,” Winkler said. “Even though my father talked about the farm all the time and loved the farm, he wanted to expose us to a greater world.”

“I look at how blessed I have been with so many people who allowed me and encouraged me to do things and grow into the person I am,” Winkler said. “It is why All of Us is so important to me. As an ambassador, I have an opportunity to work with those who may not have a door open. I can help be that bridge, provide that opportunity.”

Share your story with All of Us

If you would like to recommend someone to be featured, please submit a suggestion to All of Us.

Are you Interested in the All of Us Research Program?

- Learn about participation in the program.

- Learn about opportunities for researchers.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services